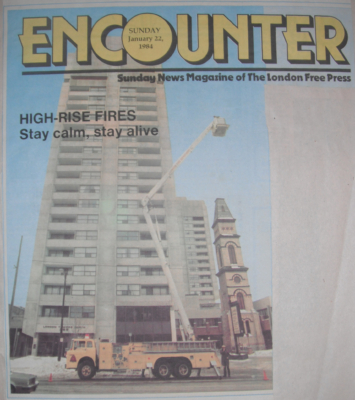

High Rise Fires, Stay calm, stay alive

It’s 2 a.m. The dispatcher leans back on his chair and stretches, still keeping one eye on the alarm panel in front of him. A panel light flashes: fire. He notes the location of the triggered alarm box and alerts the closest fire station.

At the station, an organized flurry of activity culminates as the bay doors swing open and the fire engines accelerate into the dark, electronic sirens announcing their progress, their strobe lights flashing and transmitting signals ahead to change the traffic lights on their route to green. As they arrive at the location the crew chief spots smoke pouring from the 15th floor of a high-rise apartment: a “working fire”. The chief phones for backup and orders the men to break out the high-rise kits and hook the pumper to the standpipe system.

London’s fire department is prepared to fight fires in high-rise buildings; unfortunately, many buildings and most people are unprepared.

Assistant Deputy Chief Jim Fitzgerald said people trapped in a high-rise should go out onto their balconies and wait to be rescued. Balconies are the safest spots in the buildings. He said people often panic and go into the smoke-filled halls. They get lost and die from smoke inhalation. He adds, “Ninety-one per cent of people who die in fires die from smoke and gases.”

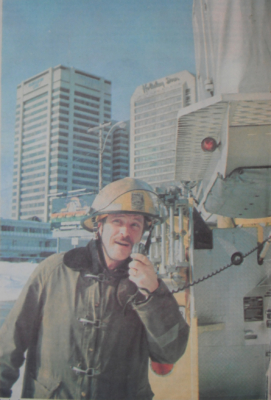

In a recent interview, Fitzgerald described the special plan his department uses when dealing with fires in high-rises.

Five “units” or trucks initially respond to the alarm. After they arrive, the chief determines if it’s a working fire – one that is not just a lot of smoke. If it’s serious the chief will call in a second alarm and another ladder truck which carries ladders and equipment for gaining entry into buildings, two more engines—vehicles which carry hoses and high pressure pumps to transfer the water from the hydrant to the fire—and a rescue unit will be dispatched.

Fitzgerald said the first engine on the scene connects to the building’s standpipe system; a system of water pipes that allows an engine to give additional pressure to the hoses being used high up in the building. As each company arrives, they break out their high-rise kits, which contain special hose lines and tools – such as axes, crowbars, chainsaws—and make their way toward the floor with the fire.

Fitzgerald said firefighters often use the elevators to get to the fire. He doesn’t advise the public to do this—heat can activate some elevator call buttons sending the elevator to the floor the fire is on, and dense smoke may interfere with the elevator’s light sensitive electric eye and stop the door from closing. But, asks Fitzgerald, “What good would a firefighter be after climbing 20 floors with all his equipment?”

Firefighters always get off the elevator at the floor below the fire and then use the stairs for their attack. Fitzgerald said a few years ago, a Toronto fire squad rode to the floor the fire was on and as the elevator door opened, they were engulfed by a surge of flames. One man died.

A main priority for the firefighters once they reach the fire is to provide it with ventilation—to let it breathe. A fire soon uses the oxygen in an area without a steady supply of air. Fitzgerald said once the fire has used up the oxygen, it begins to smoulder, but remains super-hot. “If a door or window is opened when the fire is in this state, the sudden rush of air causes the fire to explode. Firemen call this phenomenon a “flashover.”

Above ladder height in a high-rise, firefighters are often forced to grope their way through smoke-filled apartments to find a window to break open for ventilation.

Chief Fitzgerald said the London fire department’s ability to reach more than 10 stores with current equipment does not affect its ability to fight fires in high-rise buildings. He said a high-rise fire is fought from the interior, not from the outside. It makes no difference whether the fire is on the second floor or the 22nd floor.

But having to go inside a burning building presents unique hazards to the firefighter. Many of the modern petroleum-based materials used in upholstery and curtains produce cyanide gas when they burn. Even seemingly normal smoke can asphyxiate a firefighter in close confines.

One technique London’s firefighters use is to “cover” each other. As one team advances down the burning corridor, another stands ready to spray them with water should the fire trap them or become too intense.

Working in these special conditions requires expertise. Fitzgerald supervises a training complex at 746 Wellington Rd. South, that can be used to simulate any kind of fire. The abstract-looking grey concrete building has sloped roofs, flat roofs, stairwells, corridors and part of it is designed like a high-rise. During the month of June, the men may fight two or three training fires a day to prepare for the unique problems of high-rise fires.

The fire department burns straw, packing crates, old mattresses and the occasional tire to add authenticity to these drills—the men always practice with their respirators on, even when they are burning material that does not give off poisonous fumes.

Rescue procedures are a normal part of training. Fitzgerald said if the ladders can’t reach a person trapped in a high-rise fire, the firefighters will either go up the stairs, or failing that they’ll rappel down from the roof. Regardless of what method they use Fitzgerald said they always reach the stranded person. Occasionally, they reach the people too late. Fitzgerald said, “Sometimes you get into a building and they’ve been dead for hours.” Fitzgerald said people usually die because they don’t know what to do during a fire.

Inspector Art Brighton of London’s fire prevention department agrees that people should go to their balconies. Brighton also said a person who is trapped should stuff wet towels around the apartment door to prevent smoke and gases from seeping in.

Brighton believes most people are inadequately prepared to deal with fires. He thinks building manager should see that their tenants are better informed.

His department offers literature and seminars free of charge to the public on how to survive in fires. Not many people take up their offer. Brighton said according to the Ontario Fire Code, building owners must give each tenant instructions about the tenant’s responsibilities in case of a fire. A few buildings give these instructions but many that Brighton visits don’t.

Two of the major building owners in London: Esam group, owners of Cherry Hill apartments and Carleton group, owners of Lockwood Heights, do not give their tenants instructions on fire escape procedures. Kurt Nebel, Esam’s residential property manager said they give instructions to the building supervisors but not the tenants. Neither group made use of the free literature provided by Brighton’s department.

Brighton also complained that the high turnover of building superintendents poses a risk. New superintendents are of the unfamiliar with evacuation procedures and fire safety equipment. But the worst offenders are the building owners who, according to Bright, “drag their feet” in maintaining fire safety systems required by law.

Many owners even begin renting suites before alarm systems are connected although it’s a criminal offence. “They’re anxious to get the money coming in,” says Brighton. The tenant has almost no way, according to Brighton, of checking to see if the fire safety systems are properly installed.

Although a building may have fire safety equipment it may not be in proper working order. Brighton said a smoke ventilation system on the Canada Trust building in London failed to work properly during a fire in 1980. Instead of drawing the smoke out of the building, it blew it back to the first floor. Three people suffered serious injuries from smoke inhalation and nearly lost their lives.

Brighton said he would also like to see rigid laws enforced for the use of certain construction materials. Some types of foam insulation produce poisonous gases, and plywood paneling, according to Brighton, “burns like paper and enhances the spread of fire.” Fiberboard panels are another culprit Brighton would like to see controlled. He is pragmatic about these changes and feels that “it may take time to change the laws.”

Until standards are raised and laws are changed, both Brighton and Fitzgerald agree that a person’s best chance of survival is knowing what to do during a fire. If a person doesn’t panic and stays low to the floor or out on the balcony, the chances of survival are pretty good. Stay calm and stay alive, they say, and the department will take care of the rest.

Source: Encounter, Sunday news magazine of the London Free Press January 22, 1984 By Robert Osborne, freelance writer