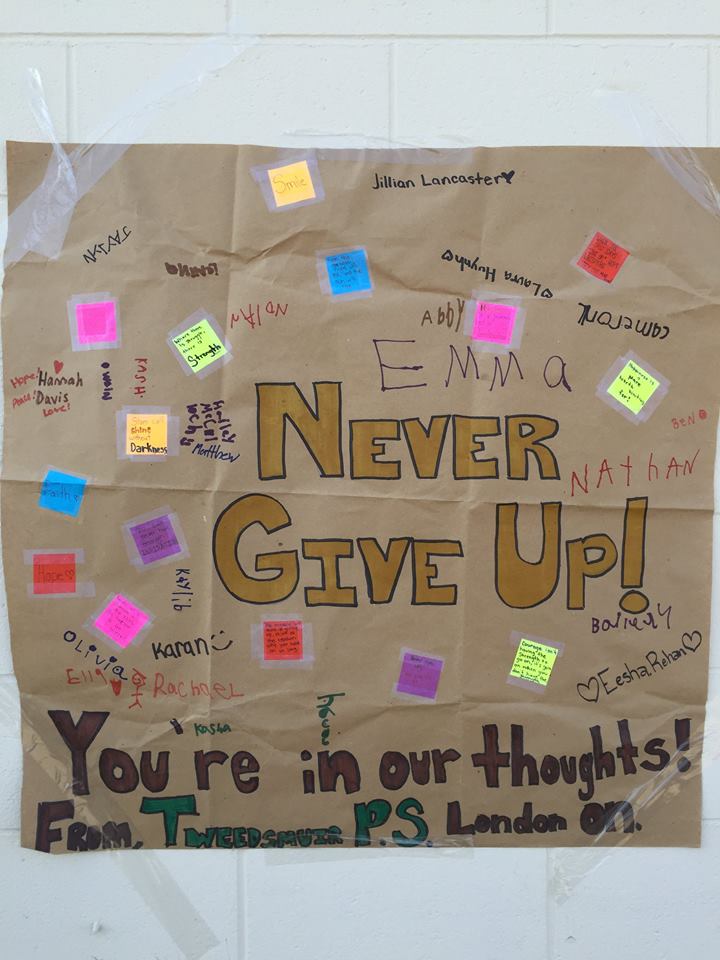

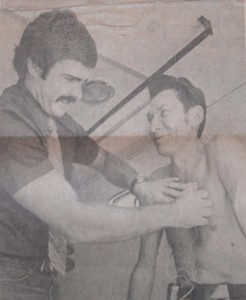

Dr. Peter Rechnitzer, at left, developed a solid appreciation for firefighters during a research project in which he and others carried out stress level test on London firefighters including Earl Smith at right. The researchers travelled to fires with firefighters to measure heart and blood levels of the men under the tension of responding to alarms. (Photo by Jeanne Graham of The Free Press)

Researchers measure tension of job

Alarm triggers firefighter stress

By NEIL MORRIS

of The Free Press

Growing up to become a fireman has filled the dreams of more than a few little boys – and maybe girls, too.

And why not? What could be more exciting than sliding down that shiny pole after an alarm, racing to your truck and hanging on for dear life as it roars across town, its siren screaming.

Little boys never thought or even knew about the other side of a fireman’s life, that of the long periods of comparative inactivity waiting for the alarm to jolt him into action once again.

Within minutes of such, he often finds himself inside a carbon monoxide-filled home in searing temperatures, perhaps under heavy physical and emotional strain trying to lift a heavy obstacle or carry an unconscious victim to safety.

What happens to this man and can his body’s control system, adaptable as it is, be made to better adapt to such instant and intense physical and psychological stress demands?

A group of University of Western Ontario medical researchers decided to find out and did so by moving directly into the working environment of London firefighters – from their firehall to the back of their fire trucks on the way to fires.

“We were interested in the problems of stress, mostly emotional stress and the stress they were under on the job,” said physiology graduate student Joe Blimkie.

University of Western Ontario physiology graduate student Joe Blimkie attaches electrodes to the chest of London firefighter Earl Smith to record his heart rate after an alarm rings and he swings into sudden, intense activity. (Photo by Jeanne Graham of The Free Press)

“We wondered if firemen, when they heard an alarm every day of their lives, were faced with a very intense stress,” added Dr. Peter Rechnitzer, a UWO clinical professor of medicine and specialist in internal medicine.

To assess stress levels, the research team studied the output of several hormones secreted by the body during periods of stress, physical or emotional.

One hormone, norepinephrine, is generally an indicator of what kind of physical stress or duress a person is experiencing such as occurs when running hard.

Epinephrine, is another hormone released into the blood when one is backed up against the wall and told he will be shot. The body releases it to help in the “fight or flight” response.

It’s all part of the adrenalin release mechanism which speeds up the heart to help one deal with a pressure situation.

The problem is that in today’s kind of society some people are going around with the constant feeling of such stress when there is nobody around threatening them.

The firefighters, about 15 volunteers, were first put through fitness training programs through a six-week period – the objective, to see if such condition could improve their body’s response to the pressures of their work.

Blood samples were later taken from them immediately after an alarm had sounded and again upon arrival at the scene of a fire, perhaps five minutes later.

Besides these tests, their heart rates were monitored, even on the fire truck on the way to a fire via electronic telemetry gear.

While data failed to show the kind of rise in hormone levels researchers expected, heart rate activity was dramatic in some cases.

The heart rates which were typical of the normal population – in the 70 beats per minute range – at the “resting state” soared sharply within 30 seconds of the alarm ringing.

According to Mr. Blimkie, the average rate increased 45 to 50 beats per minute in that first 30 seconds.

“That’s quite a significant increase in heart rate within that short a time span” he said in an interview.

A few firefighters experienced heart rate increases to as high as 175 and 180.

For unknown reasons, the fitness program did not seem to significantly influence the subsequent response of the men to sudden activity.

“It may be that a training program that would produce the kind of changes we looked for would take longer than that,” explained Mr. Blimkie.

Dr. Rechnitzer said there was “a trend in the direction” of producing lower heart rates under work load after the men had gone through the fitness program but it was not statistically significant.

But it doesn’t suggest for a moment that a program of physical fitness isn’t desirable for firefighters or any other occupational group, he stressed.

UWO exercise technologist Lili Vlach draws a blood sample from Earl Smith’s arm for analysis of his output of a hormone released during stress. Technician Margaret Roberts, centre, monitors his heart rate during the test. (Photo by Jeanne Graham of The Free Press)

In a scientific paper on their work, the UWO team which also included physiologist David Cunningham, noted that the amount of hormone response in the subjects appeared independent of the number of years of experience each had on the force.

“it may be,” they wrote, that the possibility of carrying out “an overt physical act during the alarm (running to the truck greatly reduces the degree of psychological stress, resulting ultimately in lower than anticipated epinephrine values.”

On their findings, they said it appears the alarm reaction is characterized for the most part by a sudden intensive physical arousal with only a minimal emotional arousal.

Another reason for the lower hormone levels, according to Mr. Blimkie, could be that firefighters “just weren’t that much emotionally stressed when they responded to an alarm.”

“It’s something they’re used to doing and have become accustomed to over the years.”

However it could be that blood samples were obtained too late to track the hormone level at its peak in the blood, they said.

The “half life” of the hormones – the time it takes for half the hormone to be metabolized by the body – is only 2.5 minutes. Test samples could not be obtained on the moving fire truck and had to await arrival at the fire scene several minutes later.

“Banging around (on the truck) you can lose your footing quite often,” smiled Mr. Blimkie.

The idea for the study, according to Dr. Rechnitzer, surfaced from an earlier study which showed Los Angeles firefighters had a higher incidence of heart attacks than insurance executives even though the latter had a greater number of so-called coronary risk factors such as obesity and higher blood pressures.

So the idea emerged that perhaps the recurrent sudden exposure to intense stress was potentially harmful to firemen, he said.

Mr. Blimkie said the very fact that the men’s heart rates went up dramatically immediately after the alarm sounded means “they were under quite a bit of physiological stress just in response to the alarm.”

“You’d rarely get that jogging, you’d have to sprint,” said Dr. Rechnitzer referring to the 175-to-180-beat-per-minute levels recorded in several volunteers.

The researchers have no indication that the firefighters are under any more emotional stress during the alarm period than they are at rest. “There’s no reason to say its an unhealthy job,” said Dr. Rechnitzer.

While some of the alarms were deliberately false in order to provide enough for the testing program, the men involved were unaware of the nature of the call when it came in.

The volunteers were all between the ages of 22 and 56, averaging about 35.

The researchers feel a graduated program of aerobic exercises geared to improving the over-all work efficiency of the heart would probably be good for firefighters in coping with the physical demands of their job.

One thin that did impress the team was that the firefighters “care about what they are doing.”

“They had a lot of pride in what they did and they knew they were involved in a vocation which obviously was important,” said Dr. Rechnitzer.

“I was personally really impressed with them as a group of people.”

And not without a bit of irony, the central firehall where the researchers carried out many of their medical tests was once the site of London’s medical school.

That was back between about 1880 and 1920 – no doubt just around the time when little boys were really starting to dream about becoming a fireman someday.